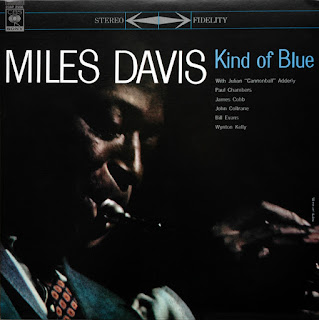

There seems something almost lame in plumping for Miles

Davis' timeless classic as the greatest jazz album ever made. It's rather like

answering Citizen Kane to the

question, What's your favourite film?

It's every would-be film critic's movie of choice. In fact, I usually answer

Bertolucci's Il Conformiste just to suggest

some independence of thought. But it's a very close-run thing anyway.

There's no such equivocation when it comes to jazz albums. I'm

happy to go along with every poll, every critic, every lover of modern jazz

when it comes to the question of best ever. Kind

of Blue is perfection on vinyl: as exquisite and as immortal as a Ming

vase. It will be there for generations of music lovers to come, long after time

has rendered questions of genre irrelevant.

Post-bop, hard bop, modern, modal jazz? Who cares? It's five

long tracks, five improvisations around particular modal scales that amount in

effect to one long meditative mood: when lights are low, when autumn leaves

begin to fall, when a gentle breeze blows through the house at the end of a hot

summer day. Whatever your imagination's fancy.

In some respects, the tracks are virtually

indistinguishable. Unless I really concentrate, I often manage

to mix up 'Blue in Green', the last track on Side 1, with 'All Blues' and

'Flamenco Sketches', the two tracks on Side 2. I can only ever identify with

confidence 'Freddie Freeloader', probably because it was recorded first (with

Wynton Kelly on piano rather than Bill Evans, whose romantic leanings dominate

the album) and 'So What', probably because it is built around one of the most

memorable hooks in popular music.

I didn't believe the hype at first. It couldn't be that good.

Besides, my feelings about Miles Davis at that point in my life were coloured

by a track from Bitches Brew on the Rockbuster sampler I used to own: 'Miles

Runs the Voodoo Down', which seemed just a little too 'out there' for my

evolving tastes. I liked the idea of Miles Davis, but I didn't know whether I

was sufficiently courageous yet.

It took a visit to New York in the mid 1980s to visit my

best friend: at a time when he and his wife were preparing to move from an

apartment they rented in Park Slope, Brooklyn to one they had just found in

Brooklyn Heights. Park Slope had not yet been as thoroughly gentrified as it

has since become. It seemed as edgy as Miles Davis's more recent music. If I

hadn't been among friends who seemed to know the lie of the land, I would've

been scared.

It was a hot and particularly wet July, with thunderstorms

and torrential downpours the signature weather of my fortnight's stay. Apart

from a brief sojourn in Long Island at my friend's mother-in-law's, where the

two of us one memorable afternoon sat on her veranda and watched the water

level of a flash flood rise inexorably and almost swallow the cars parked in

the tree-lined street, I spent much of my time exploring Manhattan on foot.

Not too far from the Woolworth Building, once in the early

years of the 20th century the tallest building in the world, I

wandered into an old-fashioned and comprehensive record shop that went by the

unprepossessing name of J&R Music. Since there was a deal on for three

Columbia records, I came out with three Miles Davis records: In a Silent Way, Filles de Kilimanjaro and... Kind

of Blue. I took them back across the Atlantic to Brighton along with a pair

of two-tone shoes I'd hummed and hawed about for far too long in a Brooklyn

shoe shop. I still have the records, of course, and I still have the shoes.

Ah! the cachet that

comes from having three of his albums with the red label of Columbia rather

than the orange of CBS. Not that anyone other than I did gave a monkey's. Still...

It took a little work on my part to learn to love the other two records, but

the first airing of Kind of Blue was enough. It transfixed me from start

to finish.

It transfixed me

from Bill Evans' opening piano motif and Paul Chambers' little bass riff that

gradually builds – with some help from Jimmy Cobb's brushes – into that

incredible compelling hook of 'So What', right through to the final plaintive

notes of Miles' muted trumpet on 'Flamenco Sketches'. Had I only known of it as

a student, I would have sat myself down between the speakers, smoked a little

herbal substance and gone off on a magic carpet ride that would have taken me

somewhere far out into the cosmos.

In fact, I was

transported to heaven and back just a year or so later, when I went to the

North Sea Jazz Festival in Den Haag. The first act was a pick-up group that

called themselves the New York All Stars: Percy and Jimmy Heath, Slide Hampton

on trombone, Jimmy Owens on trumpet, the mighty Hilton Ruiz on piano and Jimmy

Cobb, a cool, distinguished presence behind the drum kit. How I would have

loved to have chatted to him about the Kind of Blue sessions. But they

come on, they play and they wander off wither one knows not. A dressing room

perhaps somewhere in the bowels of the UN building.

This much we know.

It was made in 1959, the annus mirabilis of modern jazz: the year of

Dave Brubeck's Time Out, of Charles Mingus' wonderful Ah Um and

of most of Ornette Coleman's ground-breaking The Shape of Jazz to Come. It

was made with the two survivors of Miles Davis' great quintet of the 1950s,

Paul Chambers and John Coltrane, supplemented by Jimmy Cobb and, on most

tracks, by Bill Evans and Cannonball Adderley on alto sax.

Miles planned the

album around the romantic piano playing of Bill Evans and legend has it that he

turned up at the studio with brief sketches of the music that he heard in his

head based on the way European composers like Ravel and Rachmaninoff used

scales in their compositions. His goal, apparently, was to recreate the kind of

rural black religious music that he heard as a child on visits to Arkansas.

This is one feeling that Kind of Blue doesn't manage to achieve. And for this reason, even though So What became a permanent part of his repertoire, Miles himself felt that the album was less than a complete success. I for one certainly don't agree and there must be a few million others who don't, either. Every listen provokes the very strong feeling that together Miles and his six cohorts produced some of the most beautiful atmospheric music ever recorded.

No comments:

Post a Comment